Selected Works

Grand Union (2018)

Film Still

Written research

Invitation to the Grand Union

Research Slideshow

Grand Union (2018), an ode to pivotal postmodern dance, explores some of the issues, taboos and possibilities surrounding family in contemporary art. Over the course of a long weekend in August, nestled behind the remnants of a tall white picket fence, the family performs routine household tasks such as making coffee, reading the newspaper and washing their hair in the sink. They sometimes follow each other or do things together and occasionally function as one big nuclear family. Increasingly, they practice 60s and 70s avant-garde dance. The arc of the edited footage follows from everyday actions to dance inspired by the everyday. As they rise-and-shine and dance, this diurnal structure highlights some of the modeling, copying and other feats of representation involved in both art and growing up.

As a work-in-progress, Grand Union was selected to screen at Dance Films Association in New York (2017) and the New England Graduate Media Symposium (2016) and nominated for Platform 2016, an annual publication encapsulating the year at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

This Is the House (2016)

Unedited, Not Yet Photoshopped Documentation of the Project

Inspiration and installation

Gund Hall, Harvard Graduate School of Design

And After These Things (2018)

During a seminar at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, my classmates and I were asked to celebrate the legacy of the Bauhaus at the university. I proposed an open call to all members of the GSD community with lived experience in an environment designed by an architect affiliated with the school. Once the proposal had been selected, I sent out the call using in-school email forums. Students and staff responded with photographs chronicling their connections to a range of spaces and we found homes, so to speak, for their pictures in common areas of Gund Hall.

The installation site and mode of display for each set of photographs submitted were suggested by elements of the pictured house or landscape that resonated with the architecture of Gund. For example, photographs of tables, wall lamps, floor-to-ceiling windows, hallways and stairwells were sometimes placed next to analogous objects and architectural features at the GSD. Pictures of Christmas morning, birthdays and cooperative living took on new life amidst routine events at the school.

A play between private and institutional space animated the collective legacy we gathered. As we installed them, glossy photos of a unique two-story study almost disappeared into the Frances Loeb Library woodwork. Snapshots of college students under signature lighting fixtures hung around the corner from posters announcing campus-wide events. The expansive use of the space in many of the images challenged their celebrated design and provided a counterpoint to the GSD's contemporary, often abstract vocabulary of digital models and plans.

The photographs also conveyed markers of privilege and class--the New York City skyline, a well-manicured park--raising questions about the beneficiaries of the Bauhaus legacy and its programmatic reformulation of craft, tradition and home. Each set of photographs represented part of a household or landscape and in its specifics also pointed towards aspects of space, family and community that sit outside the frame. The resulting exhibit suggested an institutional continuity--Harvard design professionals forming a society unto itself molding its own potential future and growing up in the tillage of its past.

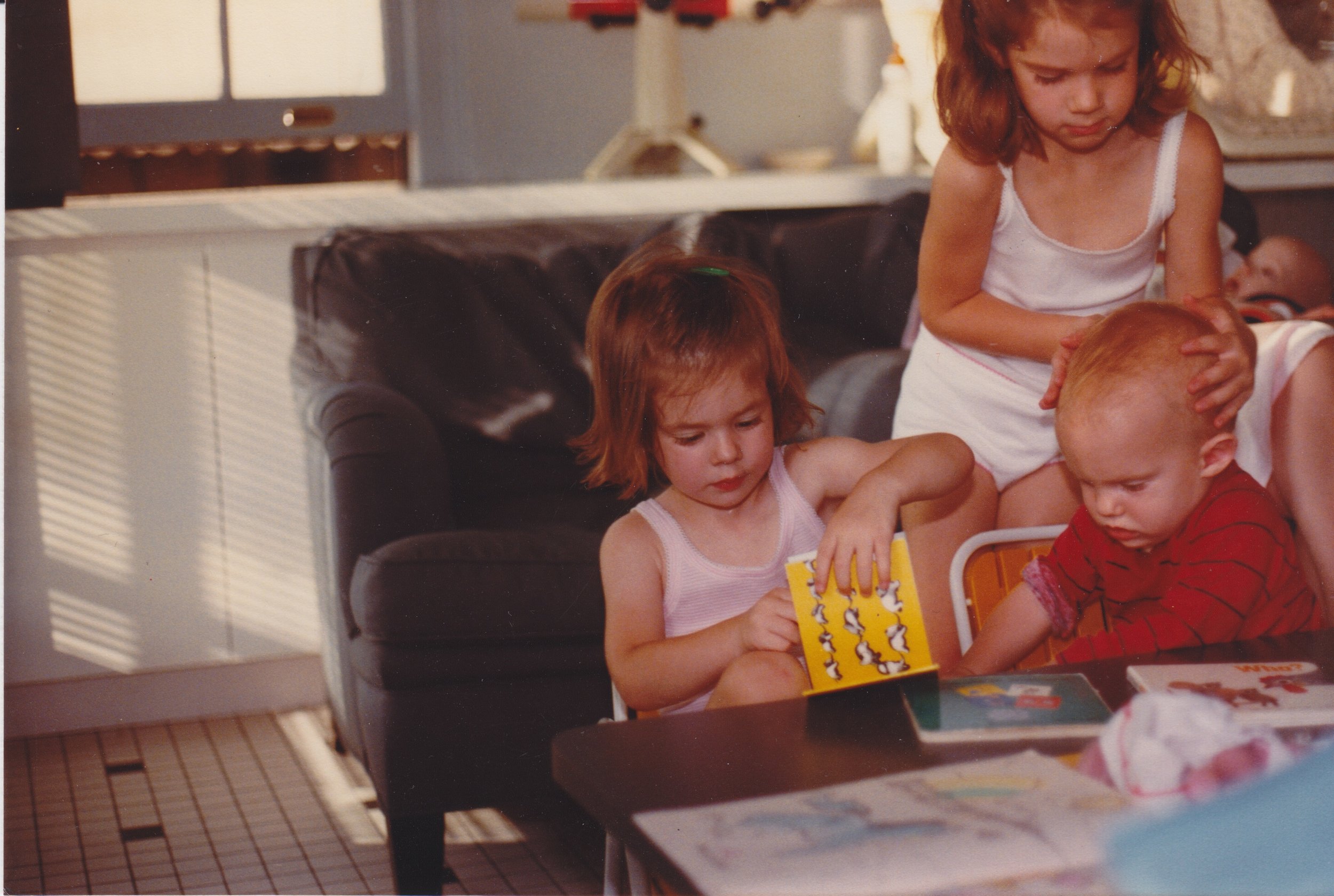

Kate Miller and Marcia Chin, New York City, 1984

The responsibility of domestic work is often shared across community and class, one form of domesticity intimately tied to the next, one care-taking arrangement nesting in another. As a mother steps away, another mother steps in. One parent goes abroad to work, another stays home. Some men cook. The woman that cares for someone else's children as if they were her own cares differently for her own children, and her own children's children. Grown children sometimes care for their caretakers in turn. How do we come to fill our role or roles in this extended family of care-taking and giving? What is the significance of our opportunities, options, and decisions in this regard? As the filmmaker visits members of her own extended family, And After These Things explores this two-fold question of how one has been cared for and how one comes to care.

And After These Things was awarded a Harvard Film Study Center Fellowship in 2016-2017.

Photograph at top from slideshow compilation of source material for the film.

Exaggerating Your Pattern and Adopting the Opposite (2018)

W2, M, W1 (2014)

Pillows

Portraits of Performers

On Walking (2010)

Untitled (Walking)

2010

The Art of Learning (WIP)

Landscape & Architecture Studies

Fruit and Things

Live Drawing

Collaborative: Phone Drawing & Video (2013)

Collaborative: Estarser Joint Symposium/ Museum of Jurassic Technology

Exaggerating Your Pattern and Adopting the Opposite is a two-channel video involving family and postmodern dance. In the first video, projected on one side of a wall, I lead my family through a Feldenkrais Method of somatic education lesson in front of the house where we spent summers growing up. The lesson is called “Exaggerating your pattern and adopting the opposite”. Side-by-side, about a window’s width apart, we take our places in a lineup that resembles a sex ed chart, except that we’re ordered according to age rather than sex or height—father, mother, sister, sister, brother, brother—holding the place of our brother Nicholas, who was Down syndrome and passed away nine years ago.

My film Grand Union (2018), which consists of interior shots of the same family and house, is projected on the other side of the wall. I intend this interior video as a kind of alternative home movie and project it at a smaller, more intimate scale than the video of the exterior of the house. In Grand Union, my family and I carry out routine household tasks such as making coffee, reading the newspaper and washing our hair in the sink. Increasingly, we practice 60s and 70s postmodern dance. The arc of the edited footage follows from everyday actions to dance inspired by the everyday.

In the early 70s, postmodern dancer Trisha Brown recounts her intention to dance “so that the audience does not know whether [she has] stopped dancing.” Playing on this idea, my family and I move in such a way that the audience cannot be sure when exactly we have started dancing. Questions of intention and motivation trouble the naturalism and highlight the performative aspects of our everyday activity. Layers of ambiguity and the sometimes arbitrary feel of the postmodern score both alienate and bond family members, creating space for the audience.

As a work in progress, Exaggerating Your Pattern and Adopting the Opposite screened at Industry Lab in Cambridge, MA as part of the group exhibition Changes (2015).

Front centre, touching one another, three identical grey urns about one yard high. From each a head protrudes, the neck held fast in the urn’s mouth. The heads are those, from left to right as seen from the auditorium, of W2, M and W1. They face undeviatingly front throughout the Play.

—Opening stage directions, Samuel Beckett’s Play (1963

W2, M, W1 pairs the text and stark set design of Samuel Beckett’s Play with somatic practice and contemporary dance. W2, M, W1 refers to Play’s stock romantic characters—a mistress, a man and a woman—and resituates their affair within the context of movement. In contrast to the urn-dwelling actors in Play, the performers in W2, M, W1 appear on exercise mats, where they simultaneously deliver their lines and explore embodied movement–from the structured sequences of the Feldenkrais Method to the more free-form partnering of Contact Improvisation. The characters speak compulsively but move with increasing fluidity, pushing the capacity for refinement and differentiation in their gestures and playing on the relationship of body and voice. In conversation with Beckett’s Play, where the habitual isolation of the characters prevents them from establishing any sense of real connection, W2, M, W1 explores the human capacity for invigorating communication and embodiment.

The Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts (CCVA) at Harvard University, the only building in North America designed by Swiss-born architect Le Corbusier, hosts the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies and the Harvard Film Archive. Until recently, with the addition of Motto Books and an invigorated exhibition program, CCVA felt empty and underutilized to me working there day in day out, with Harvard undergraduate students busy pursuing other subjects in other buildings. The uninhabited spaces of CCVA from 2010-2014 inspired the canvas building pillows pictured here. The natural oak gall dye created subtle variations that spoke to the quality and color of the buildings poured concrete floors, columns and stairs. The pillows are filled with buckwheat hulls. They are meditation pillows, in a sense. Pillows for reading, studying and resting. Pillows for folding up in a corner, folding and unfolding. The pillows are modular and portable, unlike the stairwell. They are pillows for whatever use the students find for them, a reminder to take one's physical comfort into consideration when making art, extending the gesture of a building designed with the body in mind.

Some Are Born to Sweet Delight, a more recent pillow installation, is ongoing at PRACTICE SPACE, a storefront art space in Cambridge, MA. The pillow here is inspired by wooden floors familiar to white-wall galleries, renovated homes and other locations of gentrification.

PRACTICE SPACE itself is a hybrid of the art and business that often follow one another into urban neighborhoods. I made these pillows with organic color grown cotton and indigo denim material from the leftover pile at PRACTICE SPACE, which produces and sells clothing as well as ceramics and cards, all the while hosting artists and artisans. Once completed, the pillow was placed in front of a wall-mounted iPad running bootleg footage of the Grand Union, an improvisation group beloved by New York City dancers in the 1970s. Such revolutionary art took advantage of the same expansive spaces that Soho and Chelsea galleries still maintain today.

I am currently working on a few portrait series. Yvonne, 9" x 12" acrylic on canvas board, is from the series Performers, which explores themes of femininity, partnering and mentoring. I am also painting a series called The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths, a title taken from Bruce Nauman and Mungo Thompson, which consists of portraits of artists painted in the style that Native Americans were often painted by the British. This series grapples with race, identity and issues of cultural appropriation through irony, ambiguity, and contradiction. Readers is a series of portraits of poets and fiction writers giving readings.

http://www.estarser.net/communiques/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Final-Catalog-Small.pdf

I attached a cellphone to my right hand and made a video of what that part of my body might see and hear if it could as I walked around the studio. Then I separated the footage into individual frames and used a piece of newsprint paper to cover the part of the studio that appeared in each frame, more or less. When I took the paper down after a few weeks, a little residue remained where each piece of paper had been wheat-pasted to the wall or window. With this residue, my right hand’s “perspective” of walking became a temporary part of the studio – at night, the traces of wheat-pasted paper, traces of my hand’s movement while walking – resembled the layers of lights reflected in the Carpenter Center glass.

I continued working with these same cellphone walking videos, trying to figure out how I could communicate the movement of the recordings in a series of single images or distinctly material, even recalcitrant pictures.

I attached borrowed cellphones to myself, pressed record, and walked around the perimeter of the studio. The resulting footage, projected onto a collection of pedestals, pictures the pronounced rhythm and variety inherent in walking, normally experienced as constant. The moving objects, images, sounds and changing perspectives are reminiscent of Paul Cezanne and David Hockney’s still life and also invert Bruce Nauman’s Walking in an Exaggerated Manner around the Perimeter of a Square (1967). Where Nauman adopted constraints from Minimalism, Art, Architecture and “the studio” to direct and offset his movements, Untitled (Walking) takes the body’s own measurements and movements as determining factors. Nauman creates a picture of contrasts, juxtaposing geometry – the Square – and organic form – the S Curve – while Untitled (Walking) locates geometry in the turning, self-contained circles of human movement itself. Both Walking in an Exaggerated Manner around the Perimeter of a Square and Untitled (Walking) take the rectangle of the camera as a frame.

An experience of invariance, or the ability to experience something as complicated as walking without batting an eye, is an acquired capacity. At one point, when we were babies, even our eyes bounced around; we couldn't (yet) keep them still.

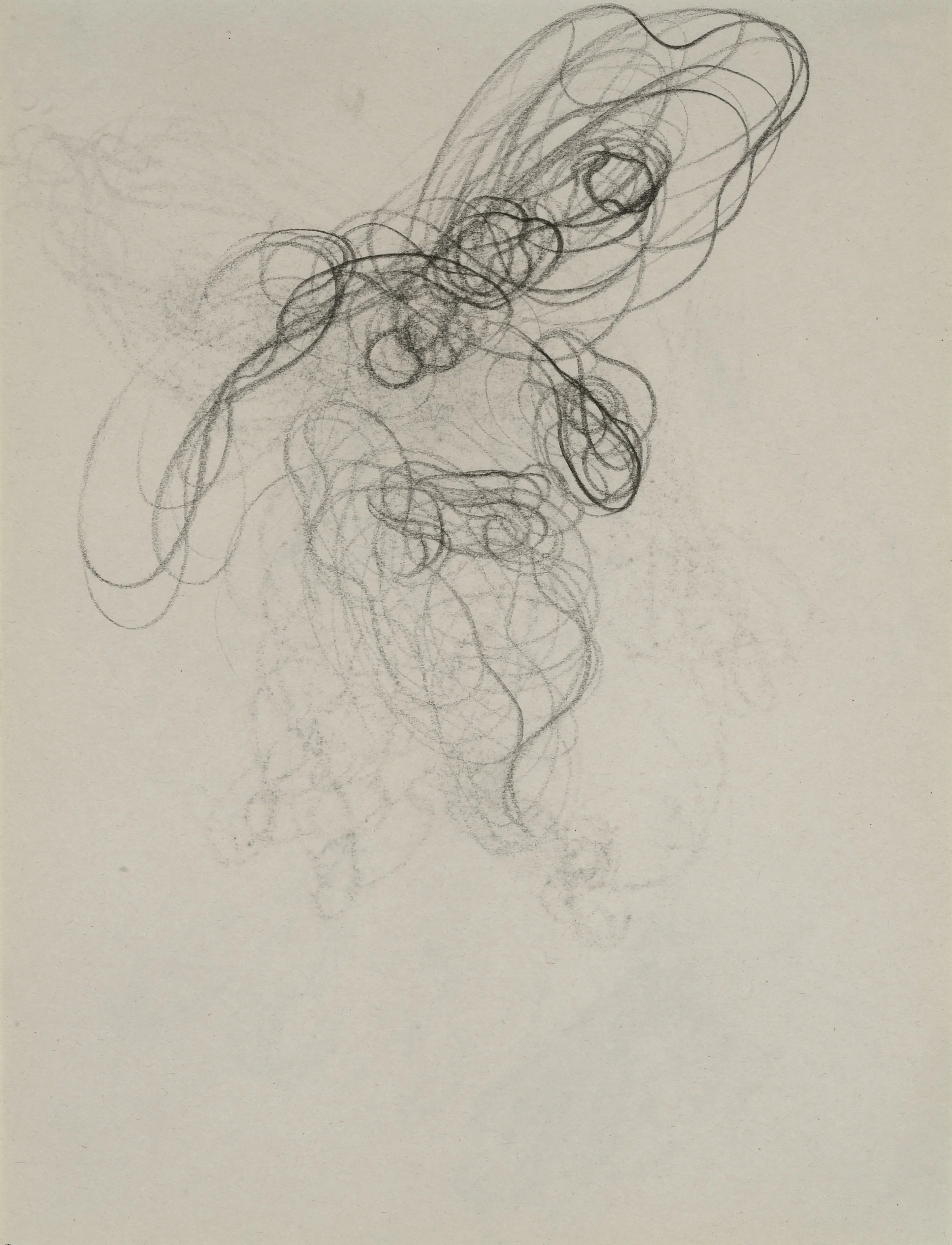

Measurement, 1984

The Art of Learning (2017) is an exploration into the elements of artistic practice that we learn without even knowing it, or without "knowing it by its name."